You say CarMEEna, I say CarMYna

You say BurAHna, I say BurAYna

CarMEEna, CarMYna, BurAHna, BurAYna

Let’s Carl the whole thing Orff

— Unknown

The outsized impact of Teutonic peuples on the sciences requires the rest of the world to get acquainted with the nuances of German pronunciation what with the umlauts, diphthongs, capitalizations, and veryLongwordscomposedofötherwordswIthnospacesinbetwëën. Berkeley chemistry majors of my vintage needed to take two terms of German so that we could read the older literature before English more-or-less took over as lingua franca. Some of us actually enjoyed it, most cursed it. Speaking of franca, the French were/are no slouches when it comes to scientific impact but we were not required to take French as part of the curriculum.

Vacky Deutscher Jens Fehlau offers a basic pronunciation course in typical vacky, flammable, and completely not-safe-for-work idiom forgoing his usual chalkboard for a MySpace page come to life. He vents justifiable rage against those profaning the great Leonhard Euler as ‘Youler’ or even ‘Wheeler’. For an existence proof of the former, see UCL mathematician Hannah Fry deadpan it repeatedly in a discussion of map projections. What in the actual f, indeed? The definitive guide to speaking the insufficiently known Emmy Noether is a major service.

Youtube Channel: Flammable Maths

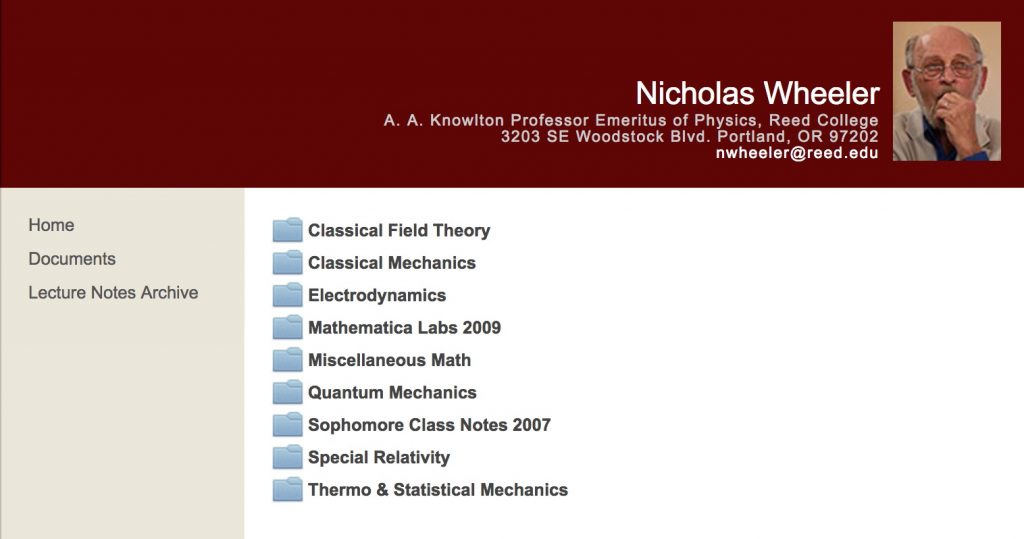

Let us now consider other Wheelers (not Youlers or Oilers) that have loomed in the physical sciences. Most famous is Princeton’s late John Archibald, coiner of terms (black hole, wormhole, it-from-bit) and who begat Feynman, Thorne, and other luminaries. There is also Reed’s Nicholas Wheeler whose lecture notes have become the stuff of legend. Now the A. A. Knowlton Professor Emeritus of Physics, Wheeler created many courses over a six decade career developing first his own approach to a topic, writing about it, and then taking his students through it. It is a pedagogical road taken by a select few. He writes,

I learned early on in my undergraduate education that while it is instructive to read, and to attend to the words of informed speakers, I cannot gain the feeling that I “understand” a subject until I have done my best to write about it. So much of my time these past sixty years—even when seemingly involved with other things—has been spent pondering the outlines of what I would write when I returned to my desk, “composing the next sentence.”

Which means that I have been engaged more often in trying to write my way to understanding than from understanding

…

When thinking through a subject in preparation for a class I have no option but to write my way through the subject, and then to lecture from my own notes. I find it much more pleasant and productive to spend an afternoon and evening writing than arguing with the absent author of a published text.

Reed has placed the original handwritten notes in their Special Archives for consultation. Fortunately, Wheeler also took pains to meticulously typeset a large fraction of these notes in ![]() and put them on his website. It is heady stuff this idiosyncratic guide through the highways, byways, and backroads of mathematical physics. Wheeler’s writing is alternately informal then precise, rigid then fluid, purposeful and then digressive. Each polished chapter contains seeds and fruits from all the others just as pieces of a hologram recapitulate the whole. There are treasures enough for many lifetimes. We can only marvel at undergraduates who had both the fortune to experience this ‘drawing out and not a putting in,’ as well as the ability to absorb and understand so much material coming from so many directions. Click the image to go the site and rejoice in each folder and its branches.

and put them on his website. It is heady stuff this idiosyncratic guide through the highways, byways, and backroads of mathematical physics. Wheeler’s writing is alternately informal then precise, rigid then fluid, purposeful and then digressive. Each polished chapter contains seeds and fruits from all the others just as pieces of a hologram recapitulate the whole. There are treasures enough for many lifetimes. We can only marvel at undergraduates who had both the fortune to experience this ‘drawing out and not a putting in,’ as well as the ability to absorb and understand so much material coming from so many directions. Click the image to go the site and rejoice in each folder and its branches.